In this guest post, the Speechmatics team walks us through what it actually takes to scale self-distillation across many GPUs. Self-distillation sounds simple on paper: a student model learns from a teacher model that is an exponential moving average (EMA) of the student’s weights. But once you try to distribute this setup, you run into a structural headache. The student updates through backprop. The teacher updates through EMA. And they need to stay perfectly in sync.

They break down three strategies they tested in production while scaling self-distillation:

Replicating both models with DDP

Sharding only the student with FSDP

Sharding both student and teacher the same way with FSDP

Their main finding is refreshingly practical: distributed training has to match the shape of the algorithm. In self-distillation, the EMA link between student and teacher means you want both models sharded identically. That alignment is what keeps the training stable and scalable.

This work was originally conducted at Speechmatics, and an extended version of this blog is available on their website.

Distillation and Self-Distillation

Knowledge distillation is a method where a student model learns from a teacher model, often by matching the teacher's outputs or intermediate representations – it is discussed in another Turing Blog post). Traditionally, the teacher is a larger, pre-trained model, and the student is smaller and initialised randomly. The goal of distillation is to transfer knowledge from the teacher to the student so the student achieves comparable performance as the teacher.

We can refer to the setup above as Fixed Teacher Distillation. Self-distillation evolves this idea, with two key differences: (1) the teacher and student share the same architecture, and (2) the teacher is not pre-trained. The self-distillation update dynamics are as follows:

Student update: The student is trained with gradient descent, minimizing a loss that aligns its outputs with the teacher's outputs. This involves a backward pass through the student network.

Teacher update: The teacher is never updated through backpropagation – it is only updated via EMA of the student, making it a lagged and smoothed version of the student. This update requires access to the student parameters.

To be more precise, the update rule for the teacher weights θteacher is given by:

θteacher = teacher(- 1) + (1 - )student(t)

where τ is a momentum coefficient (typically between 0.99 and 0.999).

The teacher is initialized by copying the initial student weights, but over time it acts as an implicit ensemble of past student models, making it more stable and less noisy than the current student. This provides richer, higher-quality targets, enabling the student to keep improving in an iterative bootstrapping loop. One influential example of this approach is DINO, which trains Vision Transformers without labels by aligning the student's predictions to those of the EMA teacher across multiple augmented views of the same image.

Distributed Self-Distillation – Replicated Student and Teacher

Training both the student and teacher model on multiple GPUs is a non-trivial task. Both networks need to process the same inputs and produce aligned outputs, but their update mechanisms differ. We focus only on data parallel techniques in this post. We won't duplicate work by others by describing different parallelisation techniques in detail. Instead, we'll refer the reader to How To Scale Your Model and the HuggingFace Ultra-Scale Playbook.

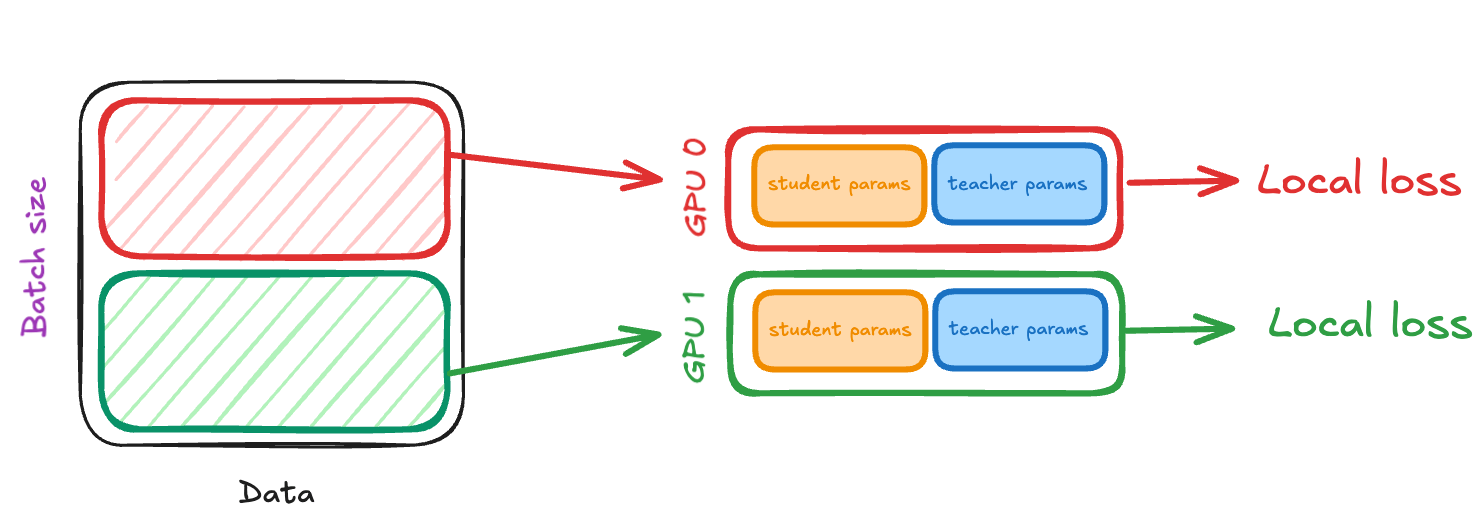

The most straightforward solution is to duplicate both the student and the teacher on every GPU, and train the student using Distributed Data Parallel (DDP). In this setup, each GPU holds a full copy of the student (with gradients and optimizer states) and a full copy of the teacher (updated via EMA of the student on that GPU). Training proceeds as follows:

Forward pass:

A training batch is split into per-gpu minibatches. Each GPU computes the teacher and student forward passes for its corresponding minibatch and its own local loss, i.e. the loss between the teacher and student outputs with respect to the data that was processed on that GPU.

Update mechanism

For the student update, one does a local backward pass on the local loss to produce a "local gradient" for each GPU. These local gradients are synchronized across GPUs via an AllReduce operation. The synchronized gradients are then used to update the student network weights across GPUs, so the student parameter update is replicated across GPUs. Once our student update is complete, the teacher EMA update updates all the teacher weights on a given GPU using the updated student weights stored on that GPU.

No custom distributed communication or parameter sharding is required here. Now let's calculate our student and teacher models' GPU memory usage with this training setup (excluding activations). If we have P parameters in our student/teacher networks we can calculate that we end up storing 14P bytes per GPU:

Component | Memory |

Student weights (BF16) | 2P |

Student gradients (BF16) | 2P |

Student Optimizer states (FP32) (Adam - 2 momentum states per parameter) | 8P |

Teacher weights (BF16) | 2P |

Total | 14P |

Depending on the model size and our GPU memory size, we may not be able to actually fit this in memory. We also repeat the same student and teacher updates on all GPUs and student and teacher weights are duplicated across GPUs. We can do better.

FSDP Student with Replicated Teacher

The student consumes the majority of memory due to gradients and optimizer states. Of the 14P parameters, 12P are dedicated to the student. We can address this by sharding our student with Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP/ZeRO-3 sharding). The teacher, requiring no gradients or optimizer states, remains fully replicated on every GPU.

Forward pass

The forward pass now proceeds similarly to before, except that since the student is sharded across our GPUs, we need to AllGather the relevant parameters during the student forward pass.

Update mechanism

One also needs to AllGather the student parameters during the student backward pass. When we combine the local gradients, we apply a ReduceScatter instead of an AllReduce, reducing and sharding the student gradients. After the local student weight update, we need to AllGather the student weights, and only then can we perform the teacher EMA update on each GPU.

By wrapping the student in FSDP, we immediately save on the memory used. If we have N GPUs, then sharding the student reduces the memory used by the student by a factor of N, thus we get a total memory requirement of 14P/N + 2P = (14/N + 2)P. This is a lot better, and can help us train bigger models, and increase our batch size.

However, notice that while we have saved some GPU memory, we have introduced 3 AllGathers (student forward, student backward, teacher EMA update). In the case of the forward and backward passes, these can be overlapped with our big matmuls. Unfortunately, we cannot hide the student AllGather in the teacher EMA update in the same way. So although we save on memory, meaning we can train larger models and increase our batch size, the train step times increase.

How much this slows down our training depends on model size and bandwidth. For instance, for H100s with NVLink interconnects (900GB/s), the AllGather will take 50ms for a model size of ~25B params.

FSDP Student and Teacher with Identical Sharding

So far we have cut down significantly on the memory requirement by FSDPing the student. No such thing as a free lunch though, as we introduced a new AllGather which may cause our GPU utilisation to take a hit when training larger models, and we're also replicating identical EMA updates across each GPU. We can address both of these problems by sharding both the student and teacher identically with FSDP. By sharding identically, we essentially mean that each GPU will hold the exact same shard of both the student and teacher networks.

Forward Pass:

The forward pass looks quite similar to before, except that we also now need to AllGather the teacher parameters in the teacher forward pass, all of which can be hidden away behind forward pass computations.

Update mechanism:

While the student backward pass remains the same, the teacher EMA update now doesn't require an AllGather and has become entirely local, as each GPU is storing the same components or shards of both the student and teacher network. Our 2 networks are stored across multiple GPUs, but as far as each GPU is concerned, it has all of the relevant parameters to perform its own update. No AllGather required! Each GPU effectively completes its 1/N portion of the EMA update, and we avoid replicating any work.

We have now gotten around having to do an extra AllGather operation, and simultaneously reduced the total work done in the EMA update by a factor of N. The reduction in total computations here is unlikely to matter much, as the teacher update is an elementwise operation that happens very quickly, and is communication bound by parameter loading bandwidth within a GPU, as opposed to the inter-gpu bandwidth that an AllGather depends on, which is approximately an order of magnitude slower. On the other hand, the removal of the AllGather can give a noticeable bump in GPU utilisation. A nice side effect is that we have also now slightly reduced our memory requirement down to 14P/N.

On a practical note, in order to identically shard our student and teacher models, we need to make sure that these have the exact same architecture. One way to achieve this is by initialising our teacher as a deepcopy of our student (or vice versa) eg. with teacher = copy.deepcopy(student). We then just wrap both models in FSDP via fsdp_model = FSDP(model, **fsdp_config). If we make sure to pass in the same fsdp_config, then PyTorch will deterministically shard these two different networks identically across our GPUs. In practice, the teacher EMA update is straightforward since each GPU only needs to access its local shards:

with torch.no_grad():

for teacher_param, student_param in zip(teacher.parameters(),

student.parameters()):

teacher_param.data.mul_(tau).add_(student_param.data, alpha=1-tau)

Since both models are identically sharded, teacher_param and student_param on each GPU correspond to the same parameter shard, making this a purely local operation with no communication overhead.

Conclusion

We have explored three approaches to scaling self-distillation training across multiple GPUs, progressively optimizing both memory efficiency and training speed. Starting from the naive approach of replicating both models (14P memory per GPU), we moved to sharding only the student ((12/N + 2)P), which saved memory but introduced an unhideable AllGather that degraded iteration time. Our final approach – identically sharding both networks (14P/N) – achieves the best of both worlds: it reduces memory usage by a factor of N while eliminating the blocking AllGather, making the teacher update purely local and restoring full training speed.

While distributed training for a single network is relatively straightforward, the addition of multiple interacting networks – whether in self-distillation, reinforcement learning with policy and value networks, or other multi-model training paradigms – introduces a new dimension of complexity around how to arrange your computational topology. The lesson here is that effective distributed training setups must respect the underlying algorithm's structure. In our case, the EMA dependency between teacher and student makes identical sharding the natural choice, keeping parameter updates local. In other multi-network settings, such as RL where networks may have different update patterns or dependencies, alternative topologies that align with those algorithmic requirements may be more appropriate. While optimizing large-scale training workflows at Speechmatics, we find that the key is designing your distributed strategy around the algorithm, not forcing the algorithm into a standard distributed pattern.

*This work was originally conducted at Speechmatics, and an extended version of this blog is available on their website. We thank Speechmatics for their insights and support of Turing Post.