Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture, or JEPA, was introduced in February 2022, when Yann LeCun firstly proposed it as the center of his vision for building AI systems that can understand and reason about the world the way humans and animals do. JEPA doesn’t predict the next token or pixel, but predicts the internal world representations – the abstract state of the world that matters most for the world models and object-driven AI, which operate at the next level of intelligence.

JEPA stands as one of the strongest alternatives to auto-regressive generative architectures, such as LLMs, that have no common sense or grounded understanding of reality, have no memory, can’t plan their answer and often hallucinate.

Note: JEPA was proposed before the LLM bonanza – not as a response to it. Later, Yann LeCun emphasized many times:

If you are interested in human-level AI, don't work on LLMs.

In recent years, we’ve seen many adaptations of JEPA across modalities, time-series models, sparse methods and others. But what we lacked was the theoretical foundation – how to build JEPA properly, and what makes a JEPA good?

Recently, we finally received it. Together with his former postdoc Randall Balestriero, Yann LeCun published what is likely one of the most important papers of the year: “LeJEPA: Provable and Scalable Self-Supervised Learning Without the Heuristics.” It finally provides the complete theory of JEPAs – and turns it into a verified practical method: LeJEPA.

You definitely need to know the key aspects behind JEPA behavior and the streamlined and scalable LeJEPA. And we’re here for you to explain them clearly and thoroughly.

In today’s episode, we will cover:

Refreshing the basics: How does JEPA work?

How JEPAs should behave

Isotropic Gaussian Embeddings

SIGReg: A unique regularization for JEPA

Implementation: What is LeJEPA?

Notable advantages and performance

Understanding the λ Trade-off

Not without limitations

What to Expect Next: Open-Source Momentum

Conclusion / Why LeJEPA matters?

Sources and further reading

Refreshing the basics: How does JEPA work?

AI has long tried to learn useful internal representations of the world that help models understand how things look, move, and change. Deep networks can now map raw data like images or signals into embeddings – compact vectors that hold meaning. The real challenge has been training those embeddings to capture the actual structure of the world rather than superficial patterns. And that’s exactly where JEPA is focused.

We explained JEPA and its connection to object-driven AI in our previous article in detail – if you want to dive deeper, we recommend reading it here. But today we’ll revisit the parts needed for general understanding and move on to LeJEPA.

So → JEPA’s (Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture) main mission is to predict the representation, or embedding, of a missing or future part of the input. Basically it’s like doing a tiny bit of time travel – peeking one moment ahead and guessing the state of the world before it happens.

It is a self-supervised architecture where the model:

Takes two related inputs (for example, two video frames: x – a current frame, y – the next frame).

Encodes them into task-relevant, abstract embeddings/representations: sx and sy.

Learns to predict the representation of the future state from the current one, using predictor module.

Image Credit: Turing Post

As a result, the model is trained by making the embeddings of two related views of the same thing agree with each other. These “views” could be any type of data: a cropped version or a blurred version of an image, a different camera angle, a masked frame in a video, or paired data like image-caption or text-code.

Crucially, JEPA does not try to predict pixels or surface details – it predicts exactly the state of the world represented abstractly. Instead of memorizing data, it learns how the world changes. As long as the two views share meaning, comparing them helps the model learn useful representations. Due to its workflow, JEPA supports object-centric understanding by modeling state transitions in abstract latent space.

This architecture also handles uncertainty, modeling the “unknown” parts of the next state in two ways:

During encoding by discarding noisy or ambiguous details.

After encoding by using latent variables (z) that represent multiple plausible future scenarios.

Overall, JEPA provides the core architectural principle for world modeling systems:

Latent state representation → what the world is

Predictive embedding → what the world will be

Modularity → separate perception, prediction, and action

Non-generative prediction → efficient modeling of long-term, structured and partially uncertain world dynamics.

Since 2022 different JEPA variant emerged, expanding JEPA to the many AI fields, like:

Multimodality: I-JEPA (image), V-JEPA and V-JEPA 2 (video), A-JEPA (audio-based), TI-JEPA (Text-Image), Text-JEPA, MC-JEPA (motion and static control).

Time series predictions, like TS-JEPA.

Combining JEPA with diffusion techniques: N-JEPA (Noise-based) and D-JEPA (Denoising JEPA).

Other types of data: 3D-JEPA, Point-JEPA (point clouds), T-JEPA (for tabular data), and even variants used in medical analysis – Signal-JEPA for EEG and ECG-JEPA.

But regardless of type, JEPA tends to cheat by giving nearly every input the same embedding which leads to collapse. This simply makes JEPA training fragile and overly complicated. Modern JEPA recipes try to prevent collapse with heuristics, such as: normalization layers, teacher–student networks, negative pairs, contrastive learning, asymmetric views + stop-gradient, complex schedules, hyperparameter tuning. However, they are quite complex and don’t guarantee the overall stability. Since collapse is a general problem of the architecture, it requires a fundamental solution.

Until now, JEPA designs have been reactive and full of heuristics. This changed with the newest member of the JEPA family – created by Yann LeCun himself: LeJEPA. It became possible because Yann LeCun and Randall Balestriero set out to rethink JEPA from the ground up, putting one key question at the center: What minimal principles should a good JEPA follow?

Before exploring LeJEPA, let’s continue with the basics – now at this updated, deeper level.

How JEPAs should behave

LeCun and Balestriero propose two simple “axioms” for JEPA:

Solve the prediction task, as it is the usual JEPA goal.

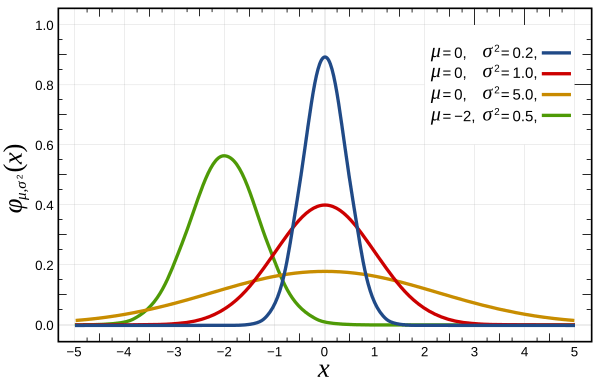

Make the embeddings follow an isotropic Gaussian distribution.

Image Credit: Normal (Gaussian) Distribution, Wikipedia

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

While the first part is well known to us, the second one is new. So why did they decide to use an isotropic Gaussian?

Isotropic Gaussian Embedding

An isotropic Gaussian distribution is a multivariate normal distribution with the same variance in all directions. Basically, it’s a clean, evenly spread cloud of points in space. Nothing is stretched or squished, and no dimension is correlated with any other. In 2D it looks like a perfect circle, in 3D a perfect sphere, and in higher dimensions the same symmetry holds. Because it’s symmetric and predictable, it’s often used in machine learning to make models more stable and the latent space easier to work with.

Easy to remember: Isotropic literally means “same in every direction”.

On the contrary, an anisotropic Gaussian distribution is like a stretched or squished version of a normal distribution. The cloud of points looks more like an ellipse (in 2D) or an elongated ellipsoid (in higher dimensions). This distribution has a “shape” with preferred directions, because different directions have different variances – some spread out more, some much less, and the dimensions can even be correlated.

Easy to remember: Anisotropic – different in different directions.

This piece is free for everyone. If you want more deep dives like this – and a clearer view of what’s actually happening in AI – consider joining Premium. Learn the basics, go deeper, stay ahead →

The researchers thoroughly analyzed the benefits of an isotropic Gaussian and showed that it’s the uniquely optimal choice for a stable JEPA. Here are the reasons why:

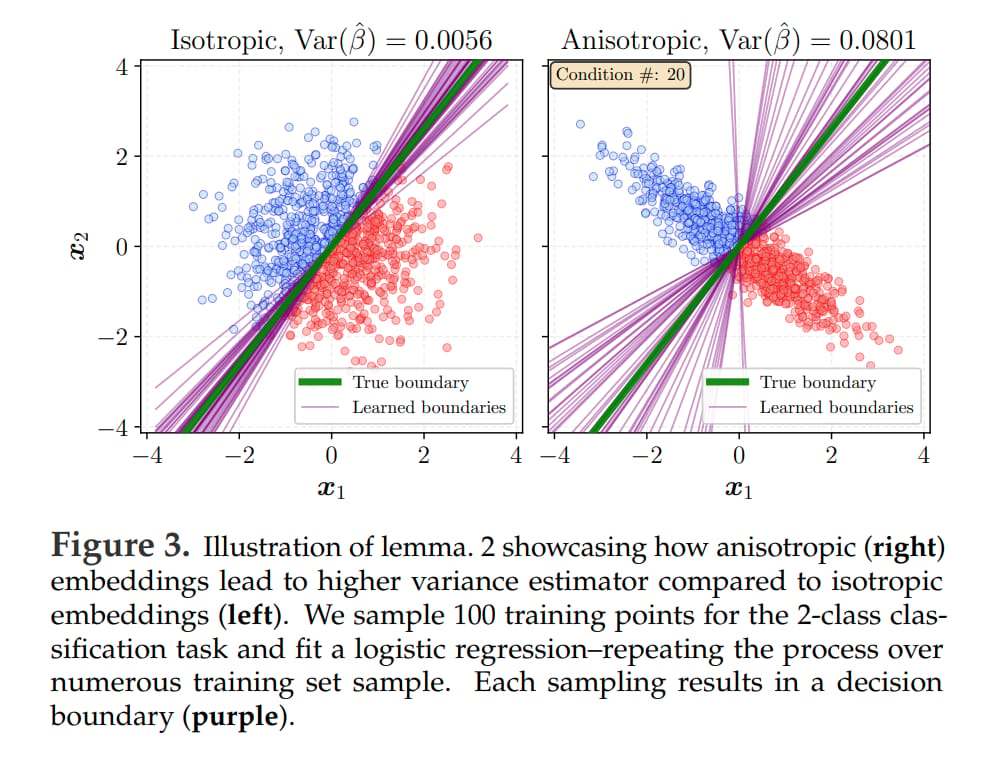

In linear probes, which check how good frozen embeddings are by training a simple linear model on top of them, anisotropy increases bias and gives much higher variance across training sets. So embeddings must be isotropic to minimize this across possible downstream tasks.

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

When measuring the integrated square bias of the predictor, among all distributions, exactly the isotropic Gaussian uniquely minimizes integrated square bias for both k-NN and kernel regression.

(k-NN, or k-nearest neighbors, method predicts a value by averaging the labels of the closest data points in the embedding space.

Kernel regression predicts a value by averaging nearby data points, giving closer ones more weight according to a kernel function.)

The higher bias and variance of anisotropic Gaussian distribution was proven in empirical checks, as well as lower alignment between true and estimated parameters.

Gathering all these aspects with the nature of isotropic Gaussian embeddings, we have the evidence that they:

Spread information evenly in all directions

Avoid overly stretched or compressed axes

Make distances meaningful and stable

Produce consistent neighborhoods, which is important for k-NN and kernels

The main question is how to keep JEPAs within the isotropic Gaussian distribution. And the researchers gave us a tool for this →

SIGReg: A unique regularization for JEPA

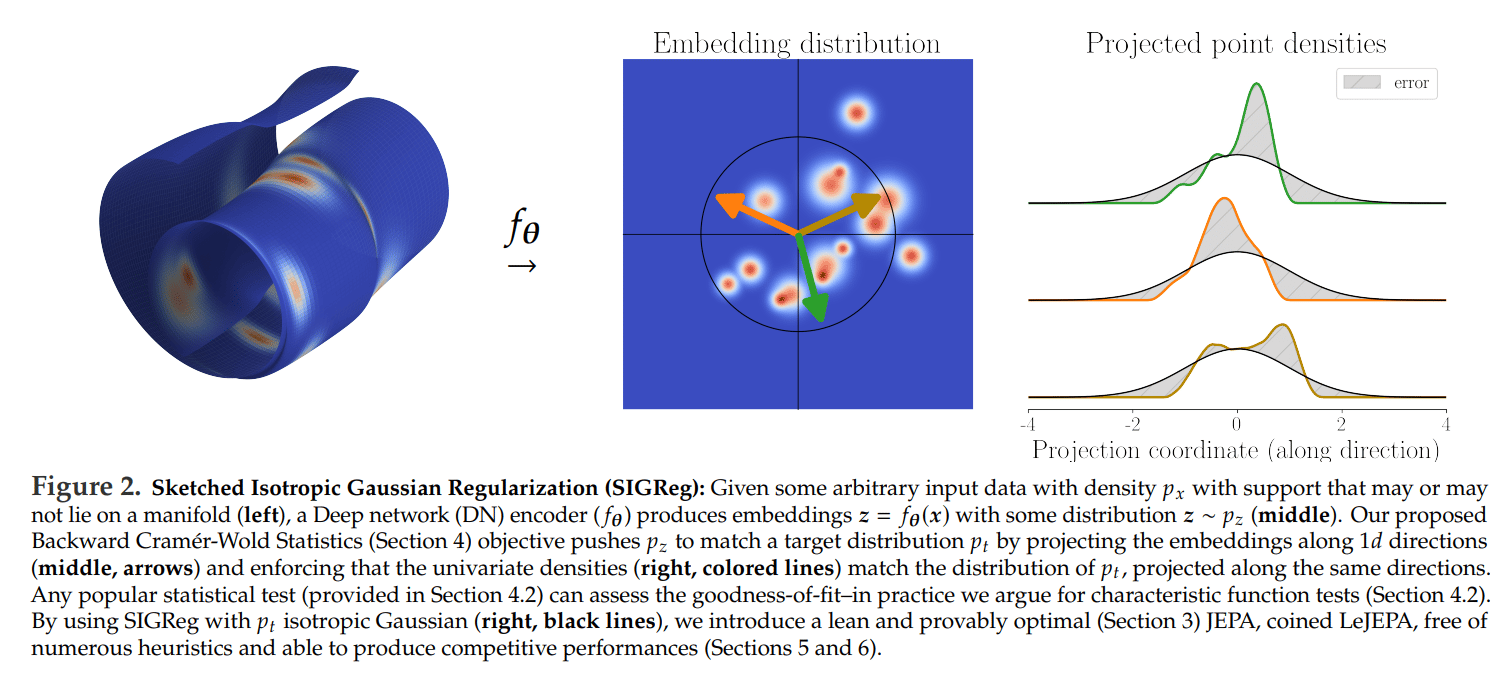

Another main contribution of the Yann Lecun’s study is a new regularization method, called SIGReg – Sketched Isotropic Gaussian Regularization, which gently pushes the model’s embeddings toward that ideal Gaussian shape.

Even though the embedding distribution may look Gaussian when you check obvious statistics, it can actually turn out to be very non-Gaussian. This is the kind of “shortcut” a JEPA might collapse into. So SIGReg becomes a “detector” of all the mismatches.

Here is how it works step-by-step:

Everything begins from the raw inputs (images, signals, videos, text, etc.). This data lives in a complex, irregular distribution (that messy cloud on the left of the figure below).

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

The neural network encoder turns each input example into an embedding. But the distribution of these embeddings is rarely neat – it can be stretched, squished, collapsed, or contain hidden degeneracies.

SIGReg acts as a regularizer during training that nudges the encoder so its embeddings gradually take isotropic Gaussian shape. Remember? – same in every direction.

Comparing two full high-dimensional distributions directly is extremely difficult. Instead of this, SIGReg:

Projects them onto many 1-dimensional directions (the arrows in the middle of the figure). Embeddings become dot products with the direction vector.

For each direction, it looks at the 1D distribution of the projected points.

Compares it to the 1D projection of the target isotropic Gaussian distribution.

Makes them match.

If all the 1-D projections match, the whole distribution matches. It is guaranteed with the Cramér–Wold theorem, which states that a multivariate distribution is fully determined by all its 1D projections.

To check whether each 1-D projection looks Gaussian, SIGReg uses a test statistic – Epps–Pulley characteristic-function test – which compares the Fourier-based signature of the projected data to that of a true Gaussian.

For each random direction, SIGReg computes this 1-D test statistic.

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

Then it averages across all directions – this is the SIGReg loss.

This SIGReg’s output becomes a regularization term added to the training loss. The encoder parameters are updated to reduce the mismatch.

So SIGReg gives a practical, differentiable, scalable, and statistically principled way to force embeddings toward an isotropic Gaussian that:

Prevents collapse automatically.

Scales linearly with data and dimension. It fixes degenerate embeddings even in 512–1024D settings with very few directions.

Stays stable and efficient even for very large embeddings.

And when you combine:

the usual JEPA predictive objective

plus this new SIGReg regularizer

… you get the most optimized JEPA variant – LeJEPA.

Implementation: What is LeJEPA?

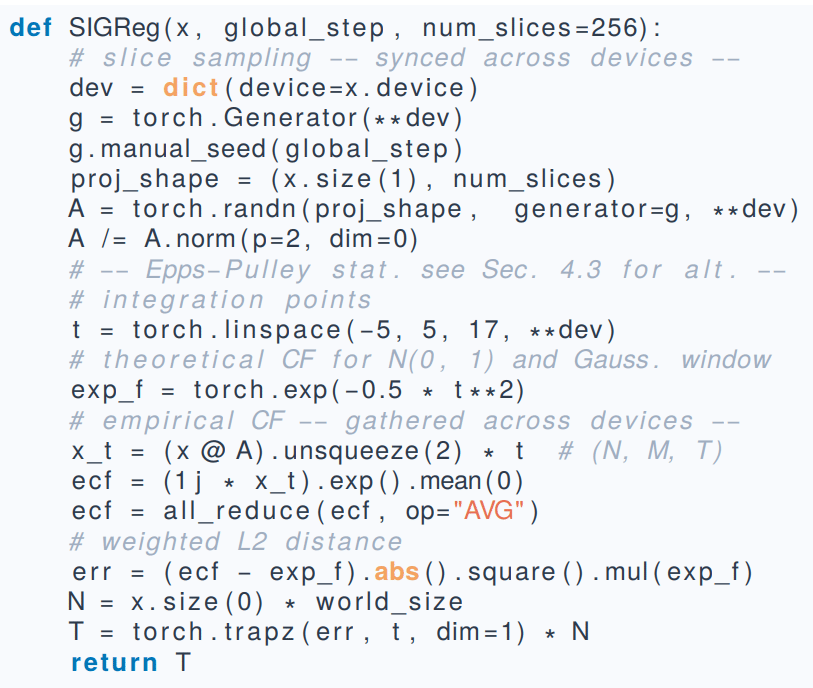

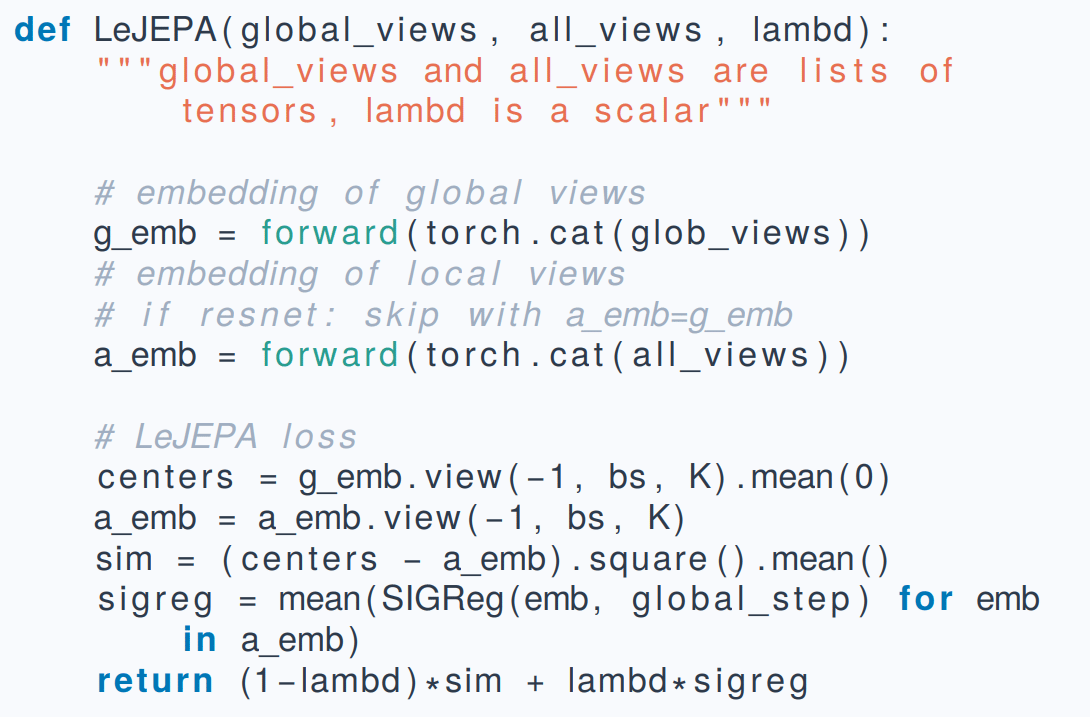

This is what we’ve been moving toward throughout the article. LeJEPA is the first JEPA implementation built on a complete theoretical foundation. Yann LeCun and Randall Balestriero put their theoretical insights directly into a very practical approach that can be implemented in just a few dozen lines of code:

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

The main idea is: LeJEPA = Prediction Loss + SIGReg Gaussian Regularizer, where:

JEPA prediction loss aligns embeddings across multiple local views of the same sample to match the global-view center.

SIGReg regularizer helps to achieve the Gaussian-shaped embedding space.

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

Here come the →

Notable advantages and performance

Putting together the final algorithm and the overall idea behind LeJEPA, we get these apparent benefits:

Only one hyperparameter λ controls the trade-off.

LeJEPA avoids all the old heuristics: no stop-gradient, no teacher–student models, no special normalization.

It prevents collapse by construction.

Offers theoretical guarantees that its embeddings are optimal for future tasks.

After comprehensive testing, several other important advantages emerged:

The biggest one is that LeJEPA is stable across architectures. It successfully trains ~50 models across 8 architecture families. All models – ResNets, ViTs, ConvNets, MaxViTs, etc. – reach 91.5%–95% top-1 accuracy on ImageNet-10 with frozen linear evaluation. Standard architectures like ResNets and ViTs work best.

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

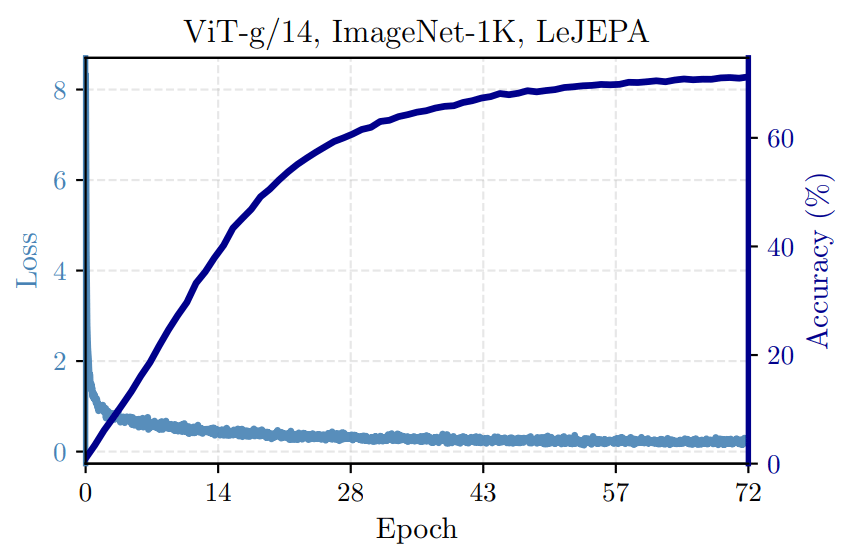

LeJEPA also scales to larger models, such as ViT-Large/14, achieving 79% linear-probe accuracy, and ViT-Huge with near-1B parameters on ImageNet-1K.

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

On the Galaxy10 dataset, LeJEPA’s in-domain self-supervised pretraining beats state-of-the-art models like DINOv2/v3 across all data sizes, from 1-shot to full supervision.

Image Credit: LeJEPA original paper

Overall, LeJEPA works across everything: hyperparameters, datasets, architectures, and sizes – without retuning.

But one implication deserves special attention: LeJEPA positions JEPA as a foundation for embodied AI and robotics. If the future of AI is embodied – robots, agents, simulation-native intelligence – then stable latent spaces matter. LeJEPA gives robotics researchers exactly what they’ve been missing: a representation space that doesn’t collapse, doesn’t drift, and consistently encodes the structure of the world. This opens the door to JEPA-based control systems, predictive planners, and world-model-driven agents.

This means that the final result of the researchers’ extensive work is a universal JEPA variant that works out-of-the-box, is stable, and competitive at scale without the usual JEPA tricks.

Understanding the λ Trade-off

The elegance of LeJEPA lies in its simplicity: λ is the only hyperparameter that needs tuning, controlling the balance between two competing objectives:

Prediction accuracy (low JEPA loss)

Distribution regularity (embeddings staying isotropic Gaussian)

This creates a fundamental trade-off:

λ too high → SIGReg dominates, forcing embeddings into a perfectly uniform Gaussian. The space becomes too regular, and embeddings lose discriminative power.

λ too low → Prediction loss dominates, SIGReg becomes too weak, and the model risks collapsing into degenerate embeddings.

λ in the sweet spot → Embeddings are spread evenly enough to avoid collapse, yet structured enough to encode meaningful distinctions.

The paper also shows that λ is robust across a wide range of values, meaning LeJEPA doesn’t require the careful hyperparameter tuning that older JEPA variants depended on. When the principles are correct, the implementation becomes forgiving.

But…

Not without limitations

The first LeJEPA tests are focused mainly on vision. It is not evaluated on multimodal, generative, or temporal JEPA setups.

Results rely mostly on linear probes, and full fine-tuning performance is not explored.

As SIGReg uses many randomly sampled 1D projections, it depends on stochastic slicing.

Importantly, while isotropic Gaussian embeddings is theoretically optimal on average, it still may not suit all tasks.

Robustness outside curated datasets like ImageNet is also unclear.

What to Expect Next: Open-Source Momentum

LeJEPA is simple enough to reimplement in a few dozen lines of code, and that usually triggers a fast open-source wave. Given LeCun’s long-standing commitment to open science, we can expect:

Rapid community adoption

Integrations into popular libraries like timm and torchvision

Multiple replication studies by Q2 2025

Ablation experiments testing LeJEPA on text, audio, and time-series

If the pattern of past Meta-FAIR releases holds, LeJEPA may become a standard self-supervised baseline sooner than people expect.

Conclusion / Why LeJEPA matters?

The study itself – likely LeCun’s last at Meta FAIR – essentially says: here’s the recipe for JEPA, go test it, build on it, make it real.

The recipe:

• The optimal embedding distribution is an isotropic Gaussian.

• Use SIGReg to achieve this Gaussian-shaped embedding space.

• LeJEPA proves the method works in practice.

One detail worth noting: domain-specific self-supervised learning (SSL) can outperform massive general-purpose foundation models when it scales cleanly. That’s exactly the gap JEPA aims to fill – a scalable SSL framework built to capture the structure of the world.

LeJEPA lands at the perfect time. The field is shifting toward world models, spatial intelligence, agent workflows, simulation-trained systems, and predictive reasoning. This work gives that movement a solid theoretical backbone. If 2024 was the year of scaling laws, 2025 may be the year we rediscover structure.

Sources and further reading

Yann LeCun’s Harvard presentation (March 28, 2024)

From Turing Post:

Collections of JEPA types with description and paper links: