This Week in Turing Post:

Wednesday / Happy New Year!

Friday / Special: Best books of 2025 – your reading list for the holidays

If you like Turing Post, consider becoming a paid subscriber or sharing this digest with a friend. It helps us keep Monday digests free →

I don’t know about you, but for me news at the end of the year is especially tiring. It’s the holidays! Everyone deserves some rest and time well spent. And if I can offer you a present this year, it would be time to read a few things that are truly worth it.

There are two things we at Turing Post prepared especially for you:

A list of 23 papers from 2025 that, even if you missed everything else, you have to know about. Alongside the papers, we asked several authors follow-up questions to clarify the implications of their work. Their responses are included here and have not been published elsewhere.

A video where a few remarkable people recommend books that shaped and influenced them.

Let’s fight slop with some really good reading. Happy New Year! Be happy 🎄

1. Here is the video (the list of books is in the description):

2. The Papers You Have to Know About with Comments from their Authors

In 2025, we saw an important shift: the research community began moving beyond an almost exclusive focus on scaling large language models, and toward a broader set of questions about intelligence in systems that are no longer purely linguistic. Attention increasingly turned to efficiency, reliability, memory, multimodal perception, and agents that operate over longer horizons and interact with the world.

Across different subfields, researchers are questioning how much progress truly depends on parameter count alone, and are exploring alternative ways to improve reasoning, long-horizon behavior, and robustness. This includes work on memory and test-time adaptation, evaluation and failure modes, reinforcement learning, and agentic systems that operate across multiple steps and tools. There is an ocean, and a little sea, of papers — and it’s easy to drown when choosing what to read.

So we decided to put together a list of our favorite (and most important) papers from 2025. If you have limited time, these 23 papers are a must-read.

I. The Rise of the Autonomous Scientist (Agents)

In 2025, agents moved from "chatting with tools" to "orchestrating discovery."

Kosmos: An AI Scientist for Autonomous Discovery – An agent that orchestrates literature search and hypothesis generation. Set a benchmark with 79.4% accuracy and at least seven actual new scientific discoveries →read the paper

Paper2Agent: Reimagining Research Papers As Interactive and Reliable AI Agents (Stanford) – Converts research papers into interactive agents via MCP. Agents can execute code, reproduce results and extend methods; experiments replicate 85 % of results and discover new splicing variants →read the paper

/our question: “When a paper’s method is later shown to be flawed or obsolete, how should a Paper2Agent behave: faithfully reproduce it, update the workflow, or surface the conflict – and who ultimately decides?”

James Zou: “If a paper contains errors or gaps, ideally, we want paper2agent to automatically surface these issues during its process of generating the paper MCP. Paper2Agent has a testing agent, whose job is to try to reproduce results in the paper or its github tutorial. So if there are mistakes in the paper's repo, then this testing agent could catch them and give feedback to the author to fix these specific issues. This way, we hope that the process of agentifying a paper would make the paper itself more robust and reproducible.”

Towards a Science of Scaling Agent Systems (Google, MIT) – The end of guesswork. This provides the quantitative rules for when multi-agent systems help versus when they just add latency and noise →read the paper

SSRL: Self‑Search Reinforcement Learning (Tsinghua) – it demonstrated that LLMs already possess latent “self‑search” ability! Plus introduces SSRL, a rule‑based reward scheme that trains models to refine knowledge internally and reduces reliance on external search while improving stability →read the paper

Agent Lightning: Train ANY AI Agents with RL (Microsoft) – A plug-and-play framework that decouples agent logic from RL training, making "RL-tuned agents" accessible to engineers, not just researchers →read the paper

II. Post-Transformer Architectures & Infinite Memory

The standard Transformer is hitting its limits. 2025 is about memory that learns at test time.

Titans: Learning to Memorize at Test-Time (Google) – Introduces neural memory that updates during inference. This allows models to scale to millions of tokens without the quadratic cost of attention →read the paper

The Dragon Hatchling: The Missing Link Between The Transformer and Models of The Brain (Pathway) – A graph-based approach to AI. It uses Hebbian learning (like the human brain) to create sparse, interpretable activations that outperform GPT-level models on long-term reasoning →read the paper

/our question: “Which real-world tasks do you expect BDH’s local-interaction approach to outperform Transformers on, and where do you anticipate it will struggle without global attention?”

Adrian Kosowski: “We designed the Dragon Hatchling (BDH) to fundamentally overcome the "memory" constraints of Transformer-based models by introducing a quickly evolving, persistent internal state. This makes BDH well-suited to tasks requiring online adaptation and reasoning over long periods of time, for processing infinite streams and learning during inference time. Major applications include life-long learning agents, log analysis, and continuous monitoring. The interpretability of BDH reinforces the usefulness of the architecture in areas where safety-critical decisions are needed, such as finance or healthcare.

Long-context transformers excel at database-like "associative recall" - finding a specific, rare token from the distant past instantly via attention heads, which makes them a good choice for needle-in-a-haystack problems. By contrast, BDH will outperform the transformer on tasks which require connecting facts and relationships observed by the model - for example, summarizing sprawling technical documents where global context aggregation is key.”

The Markovian Thinker: Architecture-Agnostic Linear Scaling of Reasoning (Mila, Microsoft) – Proves that "thinking length" and "context length" can be decoupled. It allows a small model to reason over 24k tokens using a fixed-size memory state. Introduces Delethink RL →read the paper

/our question: “Which classes of tasks do you expect to violate the Markovian assumption most severely, where fixed-size summaries lose critical information, and how would you adapt the approach there?

Milad Aghajohari: “Markovian Thinking works when the LLM carries forward what it needs to continue reasoning. We can Imagine two challenges:

1) tasks where these bits overflow the Markovian state size. For example, one hundred tokens for solving math olympiad questions is simply not enough.

2)The model failing to carry forward these bits. Our zero-shot experiments show that the reasoning that current LLMs are doing is already close to Markovian. However, we can imagine more challenging scenarios.

As a very simple example, assume a task where the model is presented with a hundred questions in a single prompt and at the end should answer all of them. The model should carry forward a list of the answers to questions it already solved. If the model fails to maintain that state, they will be erased from its context. If the zero-shot performance is low, we rely on RL to reinforce or emerge strategies that carry forward the information. However, learning such strategies via RL might be inefficient.

Note that in our own academic experiments we don’t observe an emergence of summarization or a different kind of reasoning and when we inspect the Delethink continuations they are normal reasoning traces. We can foresee that in an industry scale training, a wise context management policy emerges/resurfaces from the pretraining distribution.”

Gated Attention for LLMs: Non-linearity, Sparsity, and Attention-Sink-Free (Qwen) – A "drop-in" upgrade for Transformers. By adding simple head-specific gates, it solves the "attention sink" problem and allows for massive context extrapolation →read the paper

It’s All Connected: A Journey Through Test-Time Memorization, Attentional Bias, Retention, and Online Optimization (Google) – A unifying framework that recasts all modern memory architectures into a single theory, paving the way for the "Universal Memory" module →read the paper

Image Credit: It’s All Connected paper

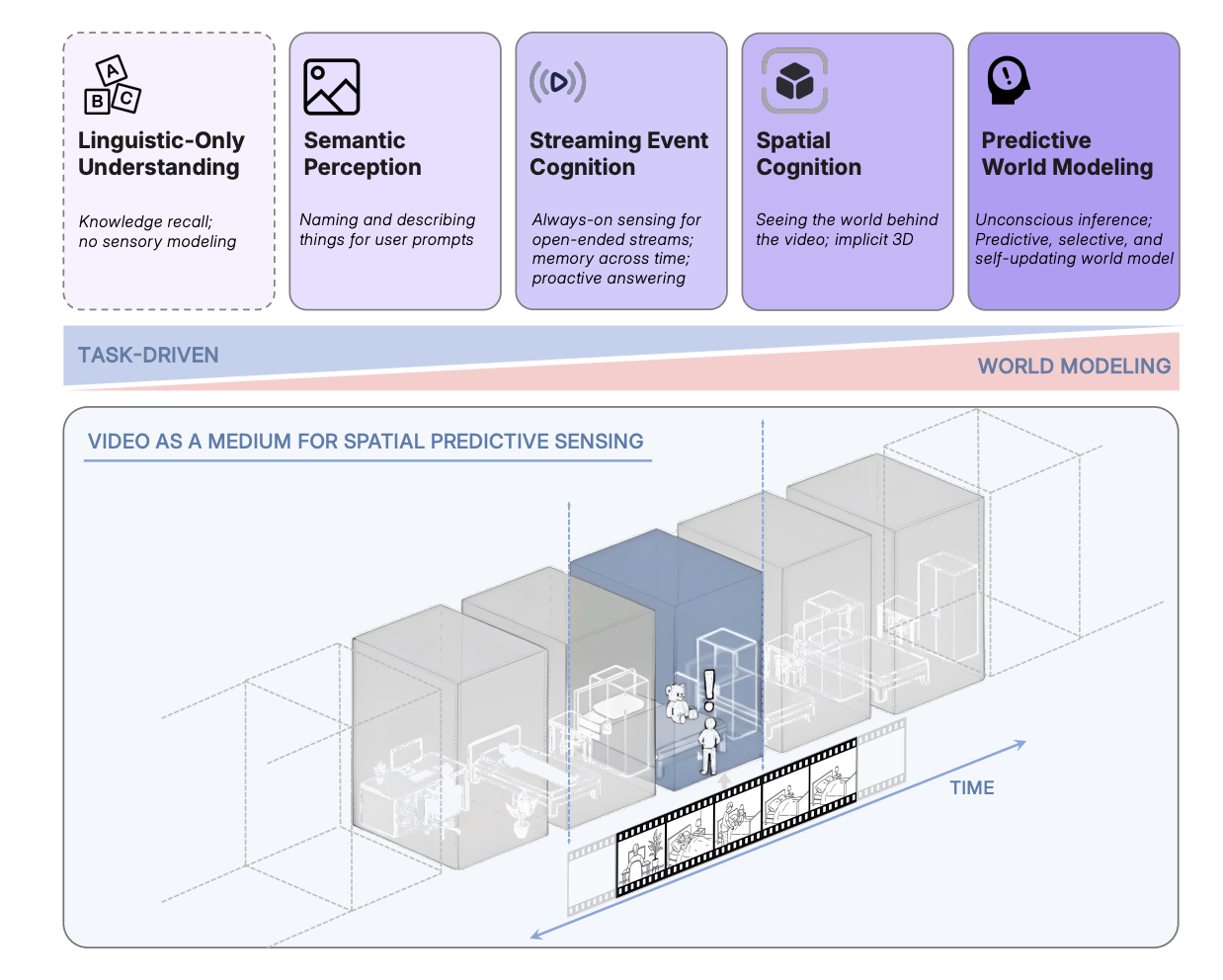

III. Beyond Tokens: Predictive World Representations

As research moves beyond language-only systems, representation learning itself is being rethought. Instead of treating perception as static tokens to be processed, these works frame intelligence as prediction over structured space, time, and latent state.

LeJEPA: Provable and Scalable Self-Supervised Learning Without the Heuristics (Meta) – The mathematical foundation for Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures. It’s hyperparameter-free and works across any modality (image, text, or video) →read the paper

Randall Balestriero: “We finally were able to have a single pretraining objective that works across any architecture, data modality, and scale – without teacher-student. This was something that many thought impossible. In fact, not only removing teacher-student was hard to believe for many, but also being able to have a single objective across architectures was quite a surprise. At a higher level though, what truly excites me about this paper is that it is the first time in recent years that an empirical breakthrough emerged from math and theory – and whose implementation is exactly the math given in the paper – no simplification, no epsilon added here and there, no hidden tricks. For years, people have given up on theory saying that scale and lots of trial-and-error is all you need to move forward. We started seeing the limits of that mindset recently, and LeJEPA demonstrated that there is a room for theory to lead the way at the SOTA level!”

/our question: “Which real-world application do you expect will be the first to adopt JEPA-style models, and how does your theoretical framework guide concrete system design there?”

Randall Balestriero: “We have already seen a quick adoption by communities outside of natural images, e.g., earth observations, satellite images, medical images and so on. The rationale is that previous methods, e.g., DINOv3 do not rely on a lot of math and are quite cumbersome to cross-validate – but at least this process has been done by Meta. So if you deal with natural images, you can just re-use Meta’s hyper-parameters for DINOv3 and get successful training! But when you look at different types of data, then you do need to cross-validate again, and that’s where the simplicity and stability of LeJEPA is hard to beat. Beyond those empirical deployments, we also saw people building on top of our theory to adapt LeJEPA to their specific data assumptions. Because every step of LeJEPA’s construction is mathematically proven and understood, it becomes trivial to modify it for a particular use-case (e.g. you expect outliers in your data and thus need to change the isotropic Gaussian for something else). The whole mechanism of LeJEPA and SIGReg remains the same (you do the 1d projections, compare the univariate densities with your target densities via the characteristic function and Epps-Pulley test).”

Cambrian‑S: Towards Spatial Supersensing in Video (NYU/Stanford) – The frontier of video understanding. It moves past "frames as tokens" and introduces "predictive coding" to give models a true sense of 3D space and time →read the paper

Image Credit: Cambrian-S paper

IV. The New Science of Scaling & RL

Throwing more data at models is no longer the only path to scaling; test-time compute and self-play have become central components.

The Art of Scaling RL Compute for LLMs (Meta) – Moves RL from "black magic" to engineering. It provides predictable curves for how much compute you need to reach specific performance milestones →read the paper

Absolute Zero: Reinforced Self-play Reasoning with Zero Data (Tsinghua) – The "AlphaZero moment" for LLMs. It demonstrates how models can generate their own tasks and training signals to reach SOTA reasoning without human data →read the paper

/our question: “In a closed-loop self-play system like Absolute Zero, how do you prevent the agent from converging on trivial or pathological behaviors, and what mechanisms ensure the curriculum continues to grow in difficulty rather than stagnate?”

Andrew Zhao: “It’s interesting that you point this out. So far, our initial method doesn’t include a mechanism to do that. The main reason is that, since we were proposing a new paradigm, we wanted to start with a clean, simple approach that still achieved strong results, and then leave room for the community to build on top of it. Our solution was not meant to address every issue, but rather to serve as a starting point for future research.

That said, your proposal is a promising research direction for closed-loop, self-improving systems. Ultimately, we want these agents to serve humans, so we should constrain learning to task subspaces that are valuable to humans and cover those subspaces as broadly as possible. One possible approach would be to regularize the task proposer using rewards that explicitly incentivize value and coverage.”

It Takes Two: GRPO is Secretly DPO – A massive efficiency win. It proves that the complex RL logic used in models like DeepSeek can be simplified into contrastive learning, saving 70% in training time →read the paper

/our question: “Do you expect this GRPO-DPO equivalence to accelerate adoption of DPO-style methods, or do you see newer preference-learning approaches emerging that could supersede both?“

Yihong Wu: “We view the equivalence of GRPO and DPO as stemming from the current binary RLVR setting. However, we expect that more powerful algorithms will likely emerge by utilizing fine-grained signals, such as ranking or continuous rewards, rather than just binary feedback.”

Is In-Context Learning Learning? (Microsoft and the University of York) – A reality check. Argues that in‑context learning is genuine learning but limited. By ablating memorization, pretraining shifts and prompt styles, the study shows ICL is sensitive to exemplar distributions and chain‑of‑thought prompting. →read the paper

/our question: “Given how sensitive ICL is to exemplar distributions, do you see a real future for “prompt engineering,” or do we need to move toward techniques like memory editing or more structured context representations?”

Adrian de Wynter: “I think that prompt engineering as it stands nowadays is slowly becoming less of a fundamental skill, especially when moving towards multiple model calls (e.g., agentic workflows) and stronger models (like RLMs) that, indeed, structure their own output/future context.

Things like edge cases can always be written down and the choice of words is significantly less relevant for output quality.

Indeed, research-wise, a lot of models have ‘handbooks’ with their preferred prompting structures. Typically it is something like JSON/Markdown with HTML sprinkled in. Nonetheless, most research works as of late tend to showcase a few prompts plus APO plus various LLMs as part of their results. Otherwise their claims will be (a) outdated tomorrow, and (b) relative to some phrasing without strong guarantees of generalisability.

This is supported by some of the results of the paper: automated prompt optimisation (APO) is effective at generating good results from the observed data (so you get good results as you prompt engineer your way through things); but it is brittle and cannot generalise (so your prompt is too specialised and likely online will not correspond fully to what you observed offline, like edge cases).

Aside, I would also argue – more controversially – that prompt engineering was never a thing per se. Writing things down and then correcting based on observations is a fundamental aspect of human communication.

Prompt engineering is basically trying multiple phrasings until something works, and the number of potential rephrasings for a given task is massive! A few years back we proved (formally) in another paper that – in general – the description of the task as output by the model suffices to get a good result.

So, ultimately, a model trained in paraphrases and variations of the same task will be able to extrapolate reasonably well what you want. Since most models in production are chat-based, this also means that there can be an intrinsic feedback loop, very much like that of an RLM or agentic workflows with a critic model.”

/our question: “What belief about AI progress did you personally change while working on this paper?”

Adrian de Wynter: “Personally, I was extremely sceptical on the capabilities of LLMs, or the autoregressive model in general. Not because of the models themselves, but because of the research. In fact, that’s precisely why I started that work: I wanted to provide strong empirical evidence at a large scale on whether these models were ‘reasoning’ over the context. After all, knowing is not the same as learning: an LLM could be trained on the whole internet, would that be sufficient to claim all-purpose generalisability?

While there were and are many works doing that (and claiming positive and negative results), they all have understandable shortcomings. These could range from no empirical work, to no robustness analysis to a few exemplars and not enough prompts being tested. All of this means very disparate results: for example, the number of papers saying that LLMs cannot solve PARITY is almost the same as those where LLMs pretty much solve it!

The paper’s results certainly changed my view, to an extent. In LLM research, there are very few absolutes. I was hoping that a massive empirical test would provide conclusive evidence of learning and generalisation capabilities, and instead what I found was that in-context learning (ICL) does constitute a form of learning. This is, however, extremely nuanced: it is a form of learning insofar as the strict mathematical definition is concerned, but it is very weak due to various brittleness conditions.

I am not going to say I’m on the side of people claiming that AI will be like the robots from I, Robot, but ICL does present properties that are way beyond what we used to work with in NLP.

That said, there are known limits to what an autoregressive model can do, such as inability to truly understand what you are saying or react to the pragmatic context. The brittleness I’ve discussed is another. Theoretical problem complexity also matters. Nonetheless, I’d argue that what we observe now is somewhere between ELIZA and sci-fi, and that makes it all the more exciting – and concerning.

(to clarify, concerned about their adoption without proper understanding of their limitations and capabilities.)”

V. Reliability: Solving Hallucinations & The "Hivemind"

As models converge in capability and training regimes, the dominant risks shift. Errors are no longer isolated mistakes, but systematic patterns shaped by incentives, evaluation practices, and the structure of reasoning itself.

Why Language Models Hallucinate (OpenAI) – The definitive 2025 paper on why LLMs guess. It argues that our current evaluation metrics force models to lie and proposes a shift toward "uncertainty-aware" objectives →read the paper

Artificial Hivemind: The Open-Ended Homogeneity of Language Models (and Beyond) (University of Washington) – A warning on homogeneity. It reveals that top models are gravitating toward a "shared average" of human thought, losing genuine creativity in the process →read the paper

/our question: “If models naturally drift toward a shared “hivemind,” which interventions do you think have the best chance of restoring genuine diversity – training data diversity, evaluation changes, or algorithmic randomness – without sacrificing reliability?”

Liwei Jiang: “Tackling this challenge requires fundamental innovations across the entire modeling pipeline, spanning data, training methodologies, model interfaces, system interaction paradigms, and evaluation. In particular, we need new training paradigms that explicitly account for the Pareto frontier between quality and diversity from the root, alongside evaluation benchmarks that explicitly and rigorously quantify diversity and creativity in open-ended generation to properly incentivize progress along these dimensions.”

Inverse Scaling in Test‑Time Compute (Anthropic) – A counter-intuitive discovery: more "thinking time" can actually make a model worse if it starts overthinking simple tasks →read the paper

The Illusion of Diminishing Returns: Measuring Long Horizon Execution in LLMs – Attributes failures in long-horizon tasks mainly to execution errors rather than limitations in reasoning, and shows how small per-step inaccuracies accumulate over time. Suggests that error-correction and verification mechanisms may be more impactful than additional scaling →read the paper

/our question: “If tiny per-step accuracy gains compound exponentially, where should research effort concentrate next: better planning algorithms, explicit error-correction mechanisms, or systematically scaling small optimizations everywhere?

Akshit Sinha: “I am currently really excited about research that is in the broad area of memory/context management. We did a small experiment in the appendix which showed promising results for context management, and recent works have come out corroborating this: including MEM1, Solving a million step task, and recursive LMs.

Handing LLMs the reins to their own context can very likely lead to large improvements for free, and can also lead to emergent self-correction, although that seems unlikely. in short: short term goals for me are context management, and long term goals would be some self-verification loop architecture for self correction and self improvement.”

VI. Efficiency & Deterministic Systems

2025 is the year AI became "Production Grade": fast, cheap, and repeatable.

Intelligence per Watt: Measuring Intelligence Efficiency of Local AI (Stanford/Together AI) – The most important benchmark of 2025. It measures accuracy divided by power, proving that local models are now 5.3x more efficient than cloud routing for most tasks →read the paper

/our question: “Which current architecture or hardware choice will look embarrassingly inefficient once IPW becomes standard?

Jon Saad-Falcon: “The most glaring inefficiency is the "route everything to frontier models" paradigm. Our data shows 77% of ChatGPT requests are single-turn chat and reasoning queries that don't require trillion-parameter models running on 700W enterprise GPUs. On the hardware side, our finding that local accelerators achieve 1.5x lower IPW than enterprise GPUs on identical models suggests significant architectural headroom; expect local silicon optimized for inference efficiency rather than peak throughput to close this gap.”

/our question: What belief about AI progress did you personally change while working on this paper?

Jon Saad-Falcon: “We underestimated how close we already are to viable local inference. Going in, we expected the accuracy gap between local and frontier models to be the main barrier, but local LMs now match or exceed cloud routing on 3 of 4 benchmarks we tested. The real surprise was the 5.3x improvement in intelligence per watt over just two years, with most gains (3.1x) coming from model improvements rather than hardware. It reframed our view: the path to ubiquitous AI isn't just about building bigger models and larger datacenters; it's about making intelligence efficient enough to run everywhere.”

Less is More: Recursive Reasoning with Tiny Networks (Samsung SAIL Montreal) – A 7-million parameter model that beats giants. It proves that "recursion" is more important than "parameter count" for solving logic puzzles like ARC-AGI →read the paper

/our question: “Does TRM’s success suggest there’s effectively no lower bound on model size for strong reasoning, or do you expect sharp diminishing returns as we keep shrinking networks further?”

Alexia Jolicoeur‑Martineau: “There is a lower-bound, but its not clear that we have reached it. I assume that we can go lower with different setups (architecture, problem, algorithm, etc.). There's always a balance to reach to prevent overfitting and underfitting. For TRM, its controlled by model size and number of recursion. For LLMs, the very specific architecture choice is preventing overfitting and then its scaled as big as possible.”

/our question: “What belief about AI progress did you personally change while working on this paper?”

Alexia Jolicoeur‑Martineau: “I thought that bigger is better with model size. But it turns out that you can prevent overfitting on small data through clever balance between recursion and model size. This is wild because regular deep learning fails to generalize normally on small datasets, but this actually allows it to work (ex: 1000 training maze, 850/1000 test maze are solved; normally AI would just memorize the solutions).”

Defeating Nondeterminism in LLM Inference (Thinking Machines) – Argues that nondeterminism in LLM inference stems not from floating‑point non‑associativity but from batch‑invariant operations and concurrency. Proposes deterministic RMSNorm, matrix multiplication and attention to eliminate nondeterministic outputs →read the paper

Curated – What we learned about memory in 2025

Follow us on 🎥 YouTube Twitter Hugging Face 🤗

We are reading (a bit of news)

Regarding Groq and Nvidia’s acqui-hire–style arrangement, reportedly valued at up to $20 billion:

NVIDIA just bought Groq for $20B. Why? by Anastasiia Nosova

3 lessons I learned in 2025 by Jim Fan

State of Consumer AI 2025 by a16z

That’s all for today. Happy Holidays! Please send this newsletter to colleagues if it can help them enhance their understanding of AI and stay ahead of the curve.

We appreciate you.