- Turing Post

- Posts

- Guest Post: How Science Actually Uses Machine Learning in 2025

Guest Post: How Science Actually Uses Machine Learning in 2025

Analysis from 5000+ research papers

In this guest post, Marktechpost shares findings from the ML Global Impact Report 2025, an interactive research landscape now available at airesearchtrends.com. Based on an analysis of 5,000+ papers from Nature journals, the report shows that while the world obsesses over generative AI, classical methods still dominate real scientific research.

In fact, 77% of machine learning applications in science rely on traditional techniques like Random Forest, XGBoost, and CatBoost, not transformers or diffusion models. The gap between AI headlines and what actually runs in labs is much larger than most people realize.

State of current media

If you open any tech newsletter or media house, you’ll be convinced that science runs on GPT-4, diffusion models, and whatever architecture dropped last week.

What we found looks very different.

When we analyzed over 5,000 scientific articles published in Nature family journals between January and September 2025, a different picture emerged entirely.

Classical ML methods, like Random Forest, support vector machines (SVMs), and Scikit-learn workflows, account for 47% of all ML use cases in scientific research.

Moreover, adding established ensemble methods like XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost, and traditional approaches, represents a dominant 77% of how scientists actually deploy ML models today.

But for neural networks and deep learning, it’s roughly 23%.

This has nothing to do with slow adoption but rather how research teams put forward their research.

In practice, researchers prioritize methods they can clearly justify during peer review. Novelty matters, but only after reliability, interpretability, and dataset sanity checks are satisfied. A Random Forest that reliably predicts protein binding affinity beats a transformer that might work better but introduces unpredictable failure modes.

When a paper depends on reproducibility and collaborators need to understand every step, novelty quickly becomes a liability. And in that context, reliability matters more than novelty.

For practitioners, the risk is obvious. Optimizing your stack around what trends on AI Twitter actively pulls you away from the methods that dominate real scientific workflows.

But who creates the tools versus who uses them?

The most consequential imbalance in ML research is who builds the tools versus who publishes with them. Nearly 90% of open-source ML tools referenced in 2025 scientific literature originate from the United States, where the foundational frameworks are powering imaging, genomics, and environmental science worldwide.

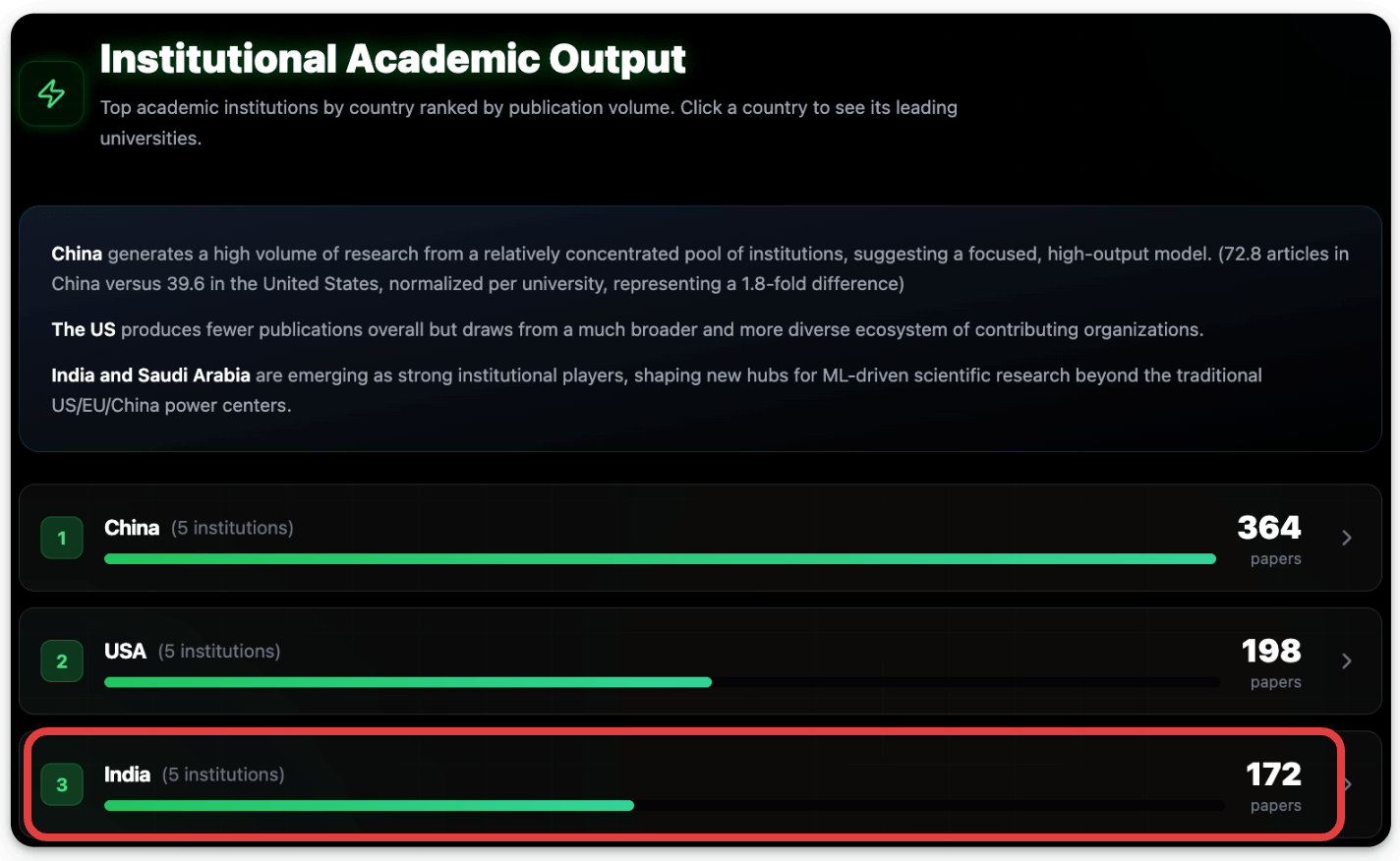

Yet the heaviest users aren’t American. China accounts for 43% of all ML-enabled papers in our dataset, compared to just 18% from the United States.

India holds third place and is climbing fast.

This imbalance shapes who sets research agendas and who executes them. Essentially, American institutions and companies build the infrastructure, while Chinese researchers publish the papers.

That said, non-US contributions to the tooling ecosystem are significant and growing. For instance:

Scikit-learn emerged from France.

U-Net, the workhorse of medical image segmentation, came from Germany.

CatBoost was developed in Russia by Yandex.

Canada produced foundational GAN and RNN architectures.

The US still dominates this layer of the stack, but it is not the only contributor.

What does this mean for the AI research community? The countries that define the frameworks shape how problems get formulated. When you inherit someone else’s tools, you often inherit their assumptions about what problems matter and how they should be solved.

Applied sciences and health research lead adoption

ML hasn’t penetrated all scientific fields equally. The heaviest adoption appears in applied sciences and health research, which are disciplines where prediction, classification, and pattern recognition map cleanly onto existing workflows.

Consider the specific applications we observed across thousands of papers:

In medical sciences, ML enables early-detection imaging, precision diagnostics, genomic sequence mapping, and mutation tracking. Cancer screening pipelines now routinely incorporate ensemble classifiers. Biomarker discovery increasingly depends on feature extraction from high-dimensional datasets.

In physical and materials sciences, researchers apply ML to advanced robotics, materials engineering, and complex physical simulations. Nanotechnology labs use neural networks to predict material properties before synthesis, saving months of experimental iteration.

In environmental sciences, large-scale Earth-observation analytics rely on ML for everything from monsoon prediction to disaster preparedness. Climate models incorporate machine learning components for pattern recognition in satellite imagery. Remote sensing has been transformed.

In agriculture, crop-yield forecasting and food systems resilience modeling now depend on ML pipelines trained on decades of historical data.

In most papers, ML appears as one step in an experimental pipeline, not the object of study.

In most domains, ML is not the focus of the paper itself. Instead, researchers publish papers about cancer or climate or crop yields that happen to use machine learning as methodology, showcasing that ML has transitioned from the research subject to the research infrastructure used in downstream problem-solving.

Collaborative research is predominant!

Contributions from the research community and our analysis make it clear that the lone genius scientist is a myth.

Most ML-enabled papers in our dataset include 2-15 institutional affiliations. Major studies rarely originate from a single organization.

But collaboration patterns differ dramatically by region.

To put this into figures:

American papers average 4.1 organizations per study, reflecting a highly distributed ecosystem spanning universities, hospitals, national laboratories, and private research institutions. Harvard Medical School leads in ML-enabled research volume, but the broader US landscape is remarkably decentralized.

Chinese papers average 2.6 organizations per study, indicating a more concentrated, high-throughput model where fewer institutions produce more output. China achieves its 43% global share through density rather than breadth, with 72.8 articles per university compared to 39.6 in the US.

Lastly, new collaboration corridors are emerging. India, Saudi Arabia, and the United States increasingly partner on applied sciences, materials research, engineering, and computer vision.

For AI practitioners building research relationships, these patterns matter. A collaboration strategy that works in the American context (distributed, multi-institutional) may need adjustment for Chinese partnerships (concentrated, institution-centric).

India’s quiet rise to third place

The report’s third-largest contributor doesn’t get enough attention: India has achieved a steep upward trajectory in ML-driven scientific output, now ranking behind only China and the United States.

What makes India’s approach distinctive is its focus on practical, scalable innovation rather than hype-driven experimentation. Indian ML research concentrates on socially relevant applications, like health diagnostics, climate resilience, fraud detection, agricultural optimization, and materials science, with local relevance.

Participation is broadening beyond elite institutions. Tier 1 and Tier 2 universities now contribute meaningfully to India’s ML research ecosystem, and a rapidly growing startup landscape is translating academic research into applied research and output.

For organizations looking to build global research partnerships, India represents an increasingly attractive option: strong technical talent, growing institutional capacity, and a pragmatic orientation toward problems that matter.

What this means for your ML strategy?

The gap discussed above mostly creates confusion, especially for practitioners who mistake visibility for impact.

If you are a researcher, don’t let trend-chasing distract from methodology that works. If Random Forest solves your problem, publish with confidence. The Nature portfolio clearly agrees.

If you are a practitioner, the tools that matter for production systems, like ensemble methods, classical feature engineering, and interpretable models, remain the tools that matter for scientific research. Investment in boring ML capabilities pays compounding returns.

If you are an ML organization, Geographic asymmetries in tool development versus research output suggest strategic opportunities. Countries consuming US-built frameworks may eventually develop alternatives.

If you are an investor or policymaker, the classical-vs-generative distribution should inform research priorities. Generative AI captures headlines, but traditional ML delivers the bulk of scientific impact.

ML is the infra layer of modern science

The takeaway is straightforward. Machine learning has stopped being the subject of research and has become the machinery behind it.

Scientists don’t write papers about Random Forest any more than they write papers about healthcare, for instance. They write papers about what Random Forest helped them discover.

As Asif Razzaq, Editor and Co-Founder of Marktechpost, put it: “This report shows that machine learning isn’t just reshaping AI, it’s reshaping science itself. The real story here is not hype, but impact, which tells that ML is now a fundamental instrument of modern scientific work.”

The 77% figure should humble anyone convinced that transformers and diffusion models define the field.

The geographic asymmetries should interest anyone thinking about how power flows through technical ecosystems. And the collaboration patterns should inform anyone building research networks in an increasingly multipolar scientific landscape.

The full interactive data is available at airesearchtrends.com, where you can explore country-level breakdowns, disciplinary distributions, and tool-by-tool analysis across 125+ countries and 5,000+ papers.

The next time someone tells you AI research is all about the latest foundation model, you’ll have 5,000 data points suggesting otherwise.

Thanks for reading!

This post was written by the Marktechpost team, specifically for Turing Post. We thank Marktechpost for sharing the ML Global Impact Report 2025 findings and supporting Turing Post’s mission to cut through the froth.

Reply